13 Oct 2025

CIH responds to the APPG for Rural Business and the Rural Powerhouse’s call for evidence: ‘Fitting rural into the devolution agenda’

We welcome the opportunity to feed into the APPG for Rural Business and the Rural Powerhouse’s call for evidence on ‘Fitting rural into the devolution agenda’. Our members work for local authorities, housing associations, and in the wider housing sector, both within and outside devolution areas. We are also active members of the Rural Housing Network (coordinated by National Housing Federation (NHF) and English Rural) and the Rural Homelessness Counts Coalition.

We have focused our response on the areas of housing and planning, as relevant to our position as the professional body for housing.

General comments

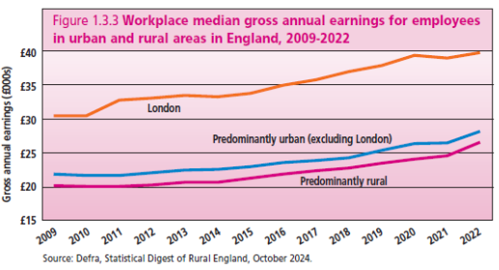

- The gradual degradation of rural communities and rural ways of life has long been evidenced. This decline has been attributed in part to proximity to economic opportunity and housing affordability. This, in turn, results in less robust public services and amenities. Demographically, an ageing population led by affluent residents and outgoing working-age adults contributes to these trends. The provision of truly affordable and secure homes is essential to counter rural decline and facilitate rural development.

- Housing is a key pillar of the devolution agenda, underpinning economic performance and the health and wellbeing of communities. The government has outlined its commitment to tackling the housing crisis and building 1.5 million new homes, including a focus on much needed social homes. We look forward to further details on the government’s vision for all types of housing in the upcoming long-term housing strategy.

- The government has implemented a range of planning reforms such as the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and Planning and Infrastructure Bill (PIB), as well as announcements of the new Social and Affordable Homes Programme, Decent Homes Standard and Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards, and a new long-term rent settlement. These demonstrate a holistic look at developing and improving both new and existing homes, and impact upon rural housing provision.

- As part of its devolution agenda, the government announced a shift towards devolved power through the English Devolution White Paper in January 2025, and the English Devolution and Community Bill introduced in July 2025, which is currently going through the parliamentary process. This Bill is likely to have wide-ranging impacts for housing delivery, funding streams, and joining-up housing, infrastructure, health, transport, and education to tackle local needs and regional priorities.

- Since these announcements, 20 new devolution deals have been created for consideration, with the ambitions for universal coverage in England. These will establish Strategic Authorities, given more control of housing and regeneration funding, with an expected regional Strategic Place Partnership. These changes are accompanied by a programme of local government reorganisation, which sees the elimination of two-tier county councils and district councils. Whilst these changes can represent an opportunity for rural areas, without the inclusion of specific rural ambitions, they may disrupt existing processes and exacerbate rural decline.

Our response focuses on CIH’s key asks for rural housing:

- Create a national, long-term plan for rural housing

- Update the definitions of designated rural areas

- Unlock the potential of Rural Exception Sites

- Boost local delivery capacity

- Ensure sufficient grant funding.

In addition to our response, we would recommend that the APPG review work outlined below for further detail and expertise on these areas:

- ‘Housing in rural areas, still a Cinderella?’ in the UK Housing Review

- Mind the Gap: How Rural Communities Are Falling Behind on Affordable Homes by ARC4

- The Case for Affordable Rural Housing by Longleigh Foundation

- Unseen, Unhoused, Unacceptable: Housing First for Rural England by English Rural

- ‘The impact of devolution on affordable housing: risk and opportunities’ by the Countryside and Community Research Institute (commissioned by the Rural Housing Network, this report is due for publication later this year and we can facilitate further discussions for the APPG).

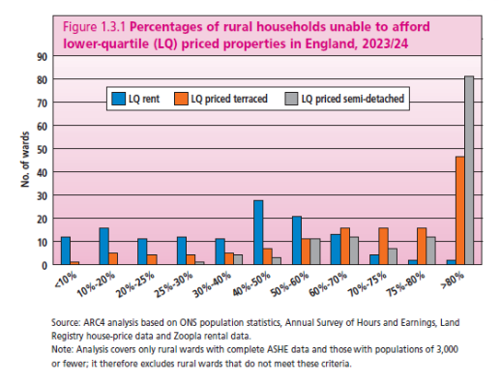

In England, almost 10 million people live in rural areas, and housing need is acute. According to analysis by ARC4, in over 60 per cent of rural wards (up to 3,000 population), almost 80 per cent of households could not afford to buy a semi-detached home in the lowest quartile of property prices. Almost half of households cannot afford the lower quartile rents in 20 per cent of rural wards. Further, even where rents might be affordable, they are scarce in supply.

In England, almost 10 million people live in rural areas, and housing need is acute. According to analysis by ARC4, in over 60 per cent of rural wards (up to 3,000 population), almost 80 per cent of households could not afford to buy a semi-detached home in the lowest quartile of property prices. Almost half of households cannot afford the lower quartile rents in 20 per cent of rural wards. Further, even where rents might be affordable, they are scarce in supply.

In urban areas, social homes comprise approximately 17 per cent of the housing stock; yet, in rural areas that proportion is nine per cent. In rural England there are over 230,000 people on social housing waiting lists in places where residents are likely to attract lower wages and have higher living costs. The impact of this is cruelly demonstrated in rural homelessness figures rising by 24 per cent from 2023-24 and the highest (and growing) fuel poverty rate.

The ability to deliver new affordable homes in rural areas is stymied due to high land values, higher construction costs, and a planning system that fails to consider affordable housing delivery in rural areas. In 2025, it was estimated that 78 per cent of local plans were out of date, further restricting the ability to meet local rural needs through the planning system. There have been new ambitious housing targets set for local authorities through the NPPF, yet these targets do not include rural or affordable housing targets, and are not tethered to assessed local need.

To tackle these issues, national planning reforms that acknowledge rural circumstances must accompany and feed through to the devolution agenda. Below we have outlined some of our key recommendations to boost rural housing delivery.

Fig 1.3.3 and Fig 1.3.3 are from the UK Housing Review, 2025

CIH supports calls for a national long-term plan for rural housing, focusing on proportionate delivery of much needed affordable housing. For a government aiming for economic growth and developing 1.5 million homes, this need cannot be ignored. The economic case for rural housing was demonstrated by modelling, which showed that for every 10 affordable new homes built in a rural area, the economy will be boosted by £1.4 million. The expected long-term housing strategy is an excellent opportunity to articulate a rural housing vision.

One key initiative to boost the delivery of rural housing is the use of rural exception sites (RES). RES are small sites on the edge of existing rural settlements that would not typically be permitted for residential housing but can be developed for affordable housing to meet rural needs. RES continue to be an underused and vital tool for delivering much needed rural housing, operating outside of the wider planning rules. Research has shown that only one in six rural households used RES, due to barriers with limited resources for planning departments, rising land costs, and local opposition.

We would encourage greater use of RES as a common method of delivering more rural housing. This would also be improved by greater engagement with local communities to demonstrate the benefits of development, as well as increasing resources for local planning departments to better facilitate the use of RES.

We support the introduction of a ‘RES Planning Passport’, which has been a proposed policy in development for some time. In theory, this policy would allow for an initial planning permission in principle for rural affordable housing schemes, to speed up the process and allow for further discussions and negotiations on the technical details of the development of a rural housing scheme.

Another vital element of boosting rural housing delivery is the role of rural housing enablers (RHEs), who provide specific expertise for RES delivery. They facilitate relationships, support community engagement, and ensure high quality design.

In our recent member engagement on rural housing, one local authority shared that they were only able to deliver a much-needed rural housing scheme in their area through the use of an expert RHE. This was vital for development and ensured that new homes were meeting local needs.

In fact, a recent evaluation report has shown that the UK government-funded programme for RHEs has led to a pipeline of more than 2,000 new affordable homes for communities.

We would encourage the greater use of RHEs, demonstrated by the continuation of national government funding for the scheme. This is particularly important to emphasise the need for RHEs as power begins to be devolved on a local level, to ensure consistency and prioritisation of meeting rural needs across different areas of the country.

In our response to the 2024 NPPF consultation, we outlined how the parameters of ‘designated rural areas’ hinder rural housing delivery. We proposed that these areas must include all parishes of 3,000 population or less, as many rural areas are currently excluded from the definition, and, so, do not benefit from rural planning initiatives.

Small sites are more likely to be available for development in rural areas. Under current rules, developers do not need to deliver affordable housing contributions on sites of ten dwellings or fewer. This limit locks rural communities out of the most prolific source of new social and affordable homes. These rules must change.

A common barrier to rural housing development is capital funding, as there are high costs in developing small rural schemes, as well as high loan costs for registered providers.

This is an area which needs further exploration by government. Some examples that have been suggested to tackle these issues are:

- Uplift grant rates for small rural schemes, as well as more flexibility

- Introduce a Rural Accelerator Loan Fund

- Provide further access to Homes England resource such as Place Making Strategies or land purchase funding, including extending eligibility for Homes England land purchase to small sites of less than 30 homes.

When a local leadership understands the needs of its diverse communities, and is provided with support to best engage with them (such as those tools named above), the devolution agenda will be equipped to deliver on local priorities and aims. This includes understanding and meeting the needs of its rural areas.

As devolution policy continues to evolve, it is essential that rural affordable housing and the evidence of what works is articulated, to ensure that all local needs are met and advocated for at a local decision-making level. The above solutions outlined in this response demonstrate national policies that must be in place to facilitate rural renewal across the country and encourage the prioritisation of rural housing when devolution deals are in place.

However, there are some potential challenges for rural housing through devolution. Rural communities can often face marginalisation from conversations on local area priorities, particularly those areas in proximity to densely populated urban centres which may require different support initiatives. Concerns have been raised for proposed unitary councils with populations over 500,000 covering large land mass of areas possessing unique characteristics and operating very differently. This could lead to rural areas having a limited voice and representation in an area’s priorities trying to meet the diverse needs of a large population.

Strategic leadership for rural housing is possible and necessary at a regional level. The devolution agenda is an opportunity for rural needs to be materially accountable within devolved councils. One such suggestion for achieving this is a Royal Town and Planning Institute (RTPI) recommendation that the Community Empowerment and Devolution Bill, (which will enforce Spatial Development Strategies across all devolved authorities) establishes rural affairs commissioners, where appropriate. Currently, the Bill at no point mentions 'rural' and its legislative basis is the Greater London Authority Act 1999. Without specific amendments to include rural considerations, devolution’s instruments risk being urban-centric and leaving rural communities behind. This could be mitigated, both in housing and across the APPG’s wider priorities, by implementing a requirement for strategic authorities to ‘have regards to rural needs’, similar to legislation such as the Levelling Up and Regeneration Act.

There are examples of where rural housing has been included in a local area’s priorities, which can be used as best practice ahead of more areas moving towards devolution. York and North Yorkshire form an Established Combined Authority with significant rural coverage and have demonstrated dedication to addressing rural housing pressures. Although they do not have a Strategic Development Strategy in place, in September 2025, alongside Homes England, they entered into a Strategic Place Partnership and have worked to develop a rural affordable housing pipeline. Further, all local authorities and registered providers in the region have committed to an Affordable Homes Standard, which aims to use collective power to improve the quality and consistency of Section 106 homes. This aims to ensure that all homes are developed at a fair price, meet space standards, are carbon efficient, and accessible. These measures will facilitate the development of sustainable houses that meet local need and show the potential of devolving housing and planning powers. At a national level, if the above measures concerning ‘designated rural areas’, and lowering the threshold for developers’ contributions were enacted, these strategic devolved schemes would be empowered to accelerate rural housing delivery further.

Interim findings from the upcoming CCRI report on rural affordable housing delivery have highlighted that, in established devolution authorities, there is currently a mixed picture concerning rural affairs. York and North Yorkshire deliver on a strong rural focus, whereas others fail to recognise or reference rural communities in their local priorities. There are concerns that in new devolved areas, urban areas will be more prominently considered, with bordering rural areas overlooked. Additionally, the report raises the concern that the disruption from devolution agendas and local government reorganisation could result in delays, confusion, and the breakdown of existing partnerships, further impacting delivering much needed rural housing.

We emphasise the need for a joined-up, holistic approach to the implementation of devolution and local government reorganisation, to ensure that structural changes, policies, and priorities meet the needs of all those living in a local area, including rural communities.

Contact

For more information on our response contact:

- Megan Hinch, policy manager, megan.hinch@cih.org

- Stephanie Morphew, policy lead, stephanie.morphew@cih.org