28 Oct 2025

CIH response to the HCLG Committee inquiry into the Affordability of Home Ownership

Summary

We welcome the opportunity to respond to the Housing, Communities and Local Government (HCLG) Committee’s inquiry into the Affordability of Home Ownership.

Our key points are as follows:

- Affordability is a crucial factor in determining potential policy solutions to provide wider access to home ownership opportunities.

- First-time buyers face considerable barriers to affordable home ownership, including high mortgage rates, house prices, and rent levels which impact ability to save for a deposit.

- Policy solutions vary from demand and supply-side options. Whilst demand-side measures will have a more immediate impact, they will push up prices if supply does not respond. Supply-side measures take longer to have an impact but help restrain house-price growth.

- We draw much of our evidence-base in this response from the UK Housing Review, an annual publication through CIH which provides up-to-date trends, data and analysis across the UK’s public and private housing sectors.

Responses to questions

First-time buyer (FTB) numbers across the UK in 2024, at around 340,000, were higher than in 2023 and close to the ten-year average. However, it has been estimated that, since 2011, there has been a cumulative shortfall of some 3.5 million FTBs because of high mortgage rates, the costs of ownership compared with renting, and other factors. Homeownership among younger households has fallen sharply as a result.

FTBs face considerable barriers. House prices have risen faster than wages, especially in London and the South East: England’s median house price rose to over eight times median earnings in 2024, up from three to four times in the 1990s. A typical five to 10 per cent deposit can now amount to £15,000–£30,000 or more, beyond the reach of many on modest incomes, a major hurdle even if an FTB can secure a 95 per cent mortgage.

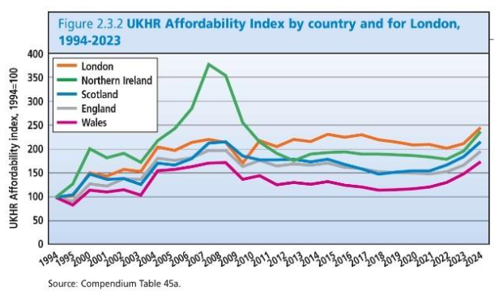

Affordability is therefore the key hurdle. The UK Housing Review measures affordability across the UK, using 1994 as its base point. It is an index based on mortgage costs relative to typical household incomes. As the chart below shows, affordability has worsened across all parts of the UK in the last three decades. There was an exceptional peak of unaffordability in Northern Ireland in the 2000s, but London is clearly identified as more unaffordable than the rest of England. However, more specific data on mortgage-cost-to-income ratios for FTBs (in the UK Housing Review’s table 44a) show that the East of England, the South West and the South East have slightly higher ratios than London, indicating a concentration of “unaffordability” for FTBs in the southern half of England generally.

Compounding the “affordability gap” are the following additional barriers facing FTBs:

- With insufficient supply of affordable homes to rent, potential FTBs are predominantly in high-rent private lettings where their ability to save for a deposit is heavily constrained.

- Growing insecurity of incomes – the gig economy – and post-pandemic inflation pressures have worsened the situation.

- Affordability checks, rightly imposed to prevent a return to the period of widespread arrears and repossessions, necessarily limit access to mortgages.

- Lower-income buyers often lack access to the “Bank of Mum and Dad” (BOMAD) available to around half of FTBs, mainly those who are better-off.

- The growth of buy to let (BtL) and of second homes/holiday homes means that FTBs face more competition in buying from the existing housing stock (although competition has been mitigated somewhat by recent tax measures).

- Low awareness of support schemes or alternatives: research from Bluestone Mortgages in September 2024 suggests only 36 per cent know about shared ownership and only eight per cent are aware of schemes like Deposit Unlock.

Government schemes to assist FTBs, though they have made an important contribution, have not been sufficient to close the affordability gap.

Many lower-income households are offered shared ownership (S/O) as their only route onto the housing ladder, but affordability concerns, leasehold complexities, and uncertainty about long-term equity gain can deter uptake or leave buyers financially stretched. This is especially the case in the most pressured areas where S/O flats predominate (in London the split is 80/20 flats to houses, elsewhere its 60/40 houses to flats).

It is useful to categorise potential options in terms of whether they are aimed at boosting demand or at boosting supply.

Demand-side policy options include tax incentives (e.g. relaxing stamp-duty land tax), subsidising deposits (as in Help to Buy), incentivising savings (e.g. with the Lifetime ISA) and providing mortgage guarantees. These measures, or a combination of them, give FTBs more buying power.

Supply-side options include financial incentives for housebuilding generally, and grants, loans or guarantees for specific schemes such as shared ownership, Rent to Buy and First Homes. Wider supply-side measures such as strengthened Section 106 obligations might also assist.

Right to buy might be regarded as a hybrid – both a supply-side and demand-side measure – specifically aimed at FTBs living in council homes. However, with recent government changes to right to buy, which CIH supported, it is expected that eligibility for and use of this scheme will be considerably reduced.

A variant on supply-side measures is tax or regulatory action to make more of the exiting stock available to potential FTBs. For example, given that FTBs face competition in buying second-hand homes, regulatory or fiscal disincentives might be employed to reduce that competition, e.g. restrictions on holiday lets, recent taxation changes aimed at reducing the competitiveness of BtL purchasers, or the recently lowering of ‘stress tests’ for mortgages.

It is worth noting that the Help to Buy (HtB) equity loan scheme had a significant impact. The UK Housing Review 2024 said that its “contribution to assisting first-time buyers cannot be understated,” although of the 328,346 borrowers the UK Housing Review estimated only around 70,000 could not have bought at all without HtB. The National Audit Office (NAO) reported that 37 per cent of homes bought with HtB would not have been built without the scheme.3 A Bank of England working paper from 2019 found that HtB was linked to increases of six to eight per cent in new-build house prices.4 HtB was also heavily criticised as providing windfall profits for developers.

There is a broader issue about the role of the Bank of England (BoE) and the associated regulatory system, which we addressed in the UK Housing Review 2025. In short, the regulatory system based around the BoE takes insufficient account of the impact of its decisions on the housing market generally, and on FTBs in particular. This argument is developed fully in the UK Housing Review (Stephens, M. (2025) “The Bank of England and housing: time for a debate”, in UK Housing Review 2025. Coventry: CIH),5 and it would be helpful if the Select Committee were to refer to it.

Clearly, a combination of demand- and supply-side measures normally applies at any one time, creating difficulties in providing good evidence on which measures are most effective. However, there is plentiful evidence that demand-side measures, while having more immediate impact, will push up prices if supply does not respond. Supply-side measures take longer to have an impact but help restrain house-price growth. Examples of relevant research include these:

- A study of the effect of HtB in two different areas found that it pushed up prices and had little impact on supply in the tight London housing market, while in the Welsh border it did boost supply while having little impact on prices (Carozzi, F. et al (2024) “On the economic impacts of mortgage credit expansion policies: Evidence from help to buy,” in Journal of Urban Economics, Volume 139, 103611).

- Studies in Leeds and Milton Keynes found that increased supply restrains house-price growth and aids affordability (Lange, M. (2025) What Milton Keynes can teach us about housebuilding (www.centreforcities.org/blog/what-milton-keynes-can-teach-us-about-housebuilding/); Jones, M. (2016) Leeds City Region: undersupply to drive growth in house prices and office rents. London: Savills).

There is a consensus in the research literature (Gleeson, J. (2023) The affordability impacts of new housing supply: A summary of recent research. Housing Research Note 10. London: GLA) that increases in the supply of new housing reduce prices and rents over the long term and at city or national level, but with considerable variation over the short term and in terms of local effects. Some of this is due to a lack of good evidence and the difficulty of separating out cause and effect between different factors. For example, building new, high-priced homes might drive up costs for lower-income FTBs, or at least do little to improve their prospects. The impact of increased supply is smaller in tight markets such as London, where the gap between supply and demand is so great.

The UK Housing Review recognises that building more homes overall is important, but tenure and prices matter greatly. Increasing the supply of market-level housing can relieve pressure, but does little for low-income FTBs, unless coupled with subsidies or measures to increase affordable supply. The 2025 Review called for “a shift from demand-side subsidies to meaningful investment in social and affordable supply” to achieve sustainable affordability.

The government’s permanent mortgage guarantee scheme and wider access to high loan-to-value (LTV) mortgage products is likely to help a proportion of FTBs, especially those who cannot save for large deposits (e.g. those in the private rented sector) and those without access to BOMAD. But it is important that supply increases as well, otherwise the scheme could worsen affordability. There are other caveats about the scheme:

- The Institute of Fiscal Studies, examining Labour’s proposal (Sturrock, D. and Boileau, B. (2024) Making mortgage guarantees permanent will help some first-time buyers, but only if they can afford a bigger mortgage. London: IFS), pointed out that to take advantage of a high LTV mortgage, a potential FTB needs to have an income high enough to secure a mortgage of this size and afford the repayments. It will have a bigger effect on affordability among potential buyers in their 30s, those who have better-off parents, and those who live in the North or Midlands, rather than the South.

- CBRE’s review of the previous guarantee scheme pointed to its low impact in terms of numbers, and the fact that it benefitted low-pressure housing areas the most (McGill, M. (2023) What impact has the Mortgage Guarantee Scheme had, and how important is its extension? London: CBRE). It noted that recent higher interest rates have affected access to high LTV mortgages, and hence to the scheme.

Lenders appear rather lukewarm towards the scheme given the cost of using it and clearly the price issue has significant implications for take up. Mortgage guarantees therefore help FTBs access higher LTV mortgages, but at rates higher than for mortgages at a lower LTV ratio. However, if more lenders enter higher LTV markets as a consequence, competition may see the pricing of those loans edge down. The UK Housing Review noted last year that the number of higher loan-to-value products on the market has risen and the guarantee scheme should help to ensure this continues. A test of the scheme is therefore not only its impact in terms of take-up, but also in terms of affordability.

There is a fundamental problem in the UK that there is no reliable method of recording private sector rent payments, equivalent to the way that mortgage providers record mortgage repayments. Setting up a robust system would take time and (presumably) have cost implications for landlords, possibly without any obvious benefits for them (in a sector where a large proportion of landlords own very small numbers of properties). Nevertheless, Skipton Building Society, which is known for its innovative products, has such a “track-record” mortgage.

Rent payment history could more readily be taken into account for people applying from the social sector, where it would help tenants to move who previously might have done so through the right to buy scheme.

Schemes to take account of rent payment history operate with varying degrees of success in the US, Canada and Australia. However, comparisons with other countries must bear in mind huge differences in how different sectors operate, are regulated, etc.

Low‑deposit mortgages and track-record products help but awareness is low, and lenders are conservative in offering them.

Evidence of the effectiveness of ISAs is variable, but generally positive. Mortgage platform TEMBO found one-in-six FTBs using Lifetime ISAs (LISAs), generally those on lower incomes. They enable FTBs to buy on average four years earlier than would otherwise have been the case. Which found one-in-ten FTBs using LISAs, getting an average bonus of £747 towards their deposit.

The Treasury Select Committee recently expressed reservations about LISAs, concluding that they disadvantage people who might need access to universal credit, and noting the high penalties for early withdrawal of funds and the price cap (£450,000) which restricts FTBs in high-value areas. Since 2017, six per cent of eligible adults have opened a LISA (around 1.3 million accounts are still open). Spending on bonuses paid to account holders will cost the Treasury around £3 billion over the five years to 2029/30. The committee questioned whether this product is the best use of public money given the current strain on public finances (Treasury Select Committee (2025) Lifetime Individual Savings Account. London: House of Commons).

The evidence on the effectiveness of stamp-duty (SDLT) relief on FTB prospects is not encouraging. An official study in 2011 concluded that temporary relief did not have “a significant impact” and that most FTBs would have bought anyway (Bolster, A. (2011) Evaluating the Impact of Stamp Duty Land Tax First Time Buyer’s Relief. London: HMSO). A recent official assessment of the FTB relief in 2017 showed that it led to a 11 per cent increase in FTB transactions, but it also raised prices by one percent. The Office for Budget responsibility commented in 2017:

“We assume that a temporary relief would feed one-for-one into house prices, but a permanent one will have twice that effect. On this basis, post-SDLT prices paid by FTBs would actually be higher with the relief than without it. Thus the main gainers from the policy are people who already own property, not the FTBs themselves.”

A further difficulty in commenting on adjustments to SDLT is that the logic of the tax itself is highly questionable. As the UK Housing Review 2025 commented (Smith, S. (2025) “Housing and economic inequality: long-run trends in the UK,” in UK Housing Review 2025. Coventry: CIH):

“[SDLT] is a brake on residential mobility (and labour market clearing), distorts housing transactions, and discourages downsizing. There is an argument for removing it altogether in favour of council tax reform.”

There is therefore a strong case to be made for a radical overhaul of property taxes, in which incentives for FTBs might be considered along with other objectives, such as making property taxes much more progressive in their effects.

The government announced a range of reforms to the homebuying process in February 2025, aimed in part at assisting FTBs.

There is a precedent for offering direct help towards transaction costs: Scotland’s First Home Fund, now ended, subsidised FTBs’ legal costs as well as offering equity loans. Another option would be vouchers towards costs. However, a scheme would have to be carefully monitored, perhaps with caps on prices, to ensure that the value of vouchers is not priced into fees charged. It is questionable whether the value of such a scheme would warrant the administrative costs involved.

Account must also be taken of developing proposals from the Home Buying and Selling Council.

Recent and proposed changes to right to buy are aimed at limiting its scope and preserving low-cost rented stock; they will therefore have an inevitable impact on potential FTBs who have council tenancies.

In the past there have been schemes to help social tenants buy homes on the private market (and release rented stock), such as the Tenant Incentive Scheme (TIS) and Do-It-Yourself Shared Ownership (DIYSO). Such schemes require grant or loan finance; even so, there may be a case for revisiting such schemes to incentivise movement between tenures and free-up social sector stock, at a time of pressing needs.

The UK Housing Review 2024 pointed out that, by that year some 127,000 shared ownership (S/O) homes had been built since 2014/15, an output that constituted more than 90 per cent of those built for affordable homeownership, and comparing favourably with the 70,000 FTBs assisted by HtB who would not otherwise have bought (see above).

While S/O is at some disadvantage as it requires grant, this is at lower levels than for rented homes, with a proportion built with nil grant; the cost is also mitigated by receipts as shares are sold. In contrast, under the Labour government’s modified fiscal rules, measures such as HtB and mortgage guarantees have a lower – or even positive – effect on the government’s debt measure. S/O, however, has a direct impact in raising supply, while the effects of demand-side measures on supply are much less direct.

Buyers also face multiple costs—mortgage, rent, full repairs, and service charges—which may make S/O no cheaper than renting or full ownership. Issues with leasehold terms, complex staircasing, resale difficulties, and limited transparency also affect take-up.

Nevertheless, there is certainly an appetite for S/O (Social Finance (2023) A more consumer focused shared ownership model which will result in increased demand and supply: a discussion paper. London: Social Finance), the question is what reforms are needed to make it as attractive as possible, and a genuinely affordable and secure route to ownership. To improve S/O under the new Social and Affordable Homes Programme, CIH recommends:

- Capping rent increases and reducing repair liabilities

- Making staircasing more flexible and affordable

- Improving transparency on staircasing costs and lease terms

- Reforming resale processes to protect buyers

- Raising public awareness and support

- Lowering initial share thresholds and rent caps

- More localised and flexible eligibility

- Ensuring access to financial products such as LISAs

- Providing stronger regulatory oversight to ensure S/O genuinely remains affordable

- Having better performance data – which could in turn help lever in more private investment.

The cross-industry Shared Ownership Council (SOC), which CIH supports, has a new code which seeks to tackle some of these issues. While S/O clearly does have defects there is therefore an appetite to address them.

Developer contributions via Section 106 are an important source of S/O homes, although there is a need for balance as it also heavily supports social rent. The growth of for-profit providers brings new investment but raises concerns around prioritising returns over affordability and resident support.

The benefits to FTBs of the Renters’ Rights Bill largely apply to potential FTBs who are currently private tenants. The legislation is aimed at stabilising the sector and the rents that landlords charge: in theory, this should help future FTBs save for deposits. It may also help people to take more measured decisions about buying, if there is less pressure to leave private lettings. The Financial Times has speculated that the bill, if successful, might transform attitudes towards homeownership by making long-term rental more attractive, as it is in countries such as Germany. It is perhaps fair to say that there is a long way to go, in modernising the sector, if this is to happen.

The Draft Leasehold & Commonhold Reform Bill should make the housing market fairer by banning new leasehold homes. This will remove ground rents and escalating service charges, making properties more saleable. It may reduce the costs of entry to the sector. The benefits only apply to newly built properties after the bill is enacted, however: existing leaseholders face legal costs in moving from leasehold to commonhold, if they are to benefit from the planned legislation, and the effects are likely to be limited in the short term. The full impact will depend on the implementation of the reforms and the specific circumstances of each property and lease.

To find out more about the consultation visit parliament’s website.

To find out more about our response please contact Megan Hinch, policy manager, CIH: megan.hinch@cih.org.