29 Aug 2025

CIH’s response to the consultation on how to implement rent convergence

We welcome the opportunity to respond to the government’s consultation on how to implement rent convergence.

In our response to the previous consultation on social rent policy in December 2024, CIH called for the re-introduction of rent convergence, supported by our analysis with Savills and other partner organisations, to address the level of investment in new and existing social housing needed to deliver the government’s ambitions. We therefore welcome the government’s acknowledgement of the sector’s responses and the commitment to implement a convergence mechanism as part of the new 10-year rent settlement. In our response to the consultation questions below, we have sought to balance the need for financial stability and certainty for the sector with the affordability concerns of tenants. To inform our response, we have updated our previous analysis with Savills to look at the benefits, opportunities and potential impacts of the scenarios outlined in the consultation, plus a scenario of £3 per week convergence. This analysis was supported by housing partners, and can be found here.

In summary, our key points are:

- CIH supports the introduction of £2 per week convergence with the necessary addition of new funding for existing homes. This should ensure a balance between financial sustainability of providers and affordability for tenants. We argue that the government must support the sector in meeting new regulatory requirements, such as the Decent Homes Standard (DHS), Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES) and the introduction of the Heat Network Technical Assurance Scheme (HNTAS), alongside other measures. If the government does not commit to this additional funding, it may be necessary to implement £3 per week convergence, to ensure stronger financial viability within the sector to enable it to provide safe and decent homes for tenants. However, we would note that even this level of convergence may not be sufficient to meet the costs of forthcoming policies relating to quality and decency without an additional existing homes funding stream.

- Wider measures are also needed to financially support the sector, such as unfreezing the Local Housing Allowance rate and providing local authorities more capacity through revisiting the HRA debt settlement.

- Rent convergence must be implemented from 1 April 2026 to maximise its effectiveness and must be for at least the length of the rent settlement, 10 years, or as long as required to reach formula rents. We also reiterate the call for the government to set the settlement into legislation, to avoid policy changes over parliamentary terms which would further damage the financial certainty for providers, as seen in recent years.

- Tenant affordability must remain at the heart of the discussion on rent increases. Our members have outlined their current support initiatives for tenants, but this must also be supported by an effective, national social security system, with changes needed such as removing the two-child limit, to help those in most need.

On balance we believe social rent convergence should be capped at £2 per week, with additional funding to meet new regulatory requirements.

As stated in our previous call for convergence, it is crucial that the sector is financially viable and stable enough to invest in existing homes and build much needed new homes, in support of the government’s mission to build 1.5 million homes in this parliament. As such, it is necessary to converge all social rents to meet formula rent, and in so doing to provide greater fairness and equality across regions. We welcome the government’s commitment to introducing rent convergence which, combined with the 10-year rent policy, will significantly improve the sector’s financial viability, help to fix the foundations of a broken housing finance system, and repair the damage from years of uncertainty with frequent rent policy changes and reductions. Rent convergence will play a crucial role in supporting the sector in its mission to provide affordable homes for those who most need them. Crucially, without the introduction of at least £2 per week convergence, local authorities will continue to operate in deficit on their Housing Revenue Accounts (HRAs), which would be detrimental to local communities who rely on their vital services.

Further, supported and specialist housing providers face an acute financial crisis, with one in three having to close schemes in the past 12 months due to financial pressures. It is crucial that the government supports this sector which provides vital and life-giving services and housing to some of the most vulnerable in our society, as well as saving costs for the NHS. We highlighted these pressures and necessary solutions in our submission to the recent Spending Review.

Throughout our member engagement regarding the different scenarios outlined in the consultation, and including an additional option of convergence at a maximum of £3 per week, we have been mindful of the varying impacts between different regions, landlords, and tenant groups. Clearly, there is a range of opinions across the sector on which level of rent convergence should be chosen. CIH has reviewed these comments, along with the assessment provided by Savills (see below), and has concluded that £2 per week is the most appropriate weekly limit for convergence. We believe this balances both the sector’s financial sustainability and tenant affordability, with significant caveats on additional funding required (outlined below). We further demonstrate the impact on tenant affordability in our response to question 10.

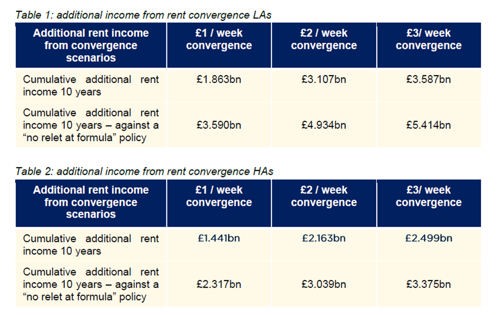

Our analysis from Savills portrays different sets of results depending on whether social landlords are already setting rents at formula level on relets, or whether they relet at previous (non-formula) rents. For the minority of individual landlords who are not reletting at formula, convergence will obviously make a bigger difference to their incomes and there is an argument that re-lets should move immediately to formula rent; see figure below, taken from page four of the Savills analysis resume.

The summary analysis indicates that convergence at £1 per week would provide circa £1.4 billion additional income for housing associations over 10 years, and circa £1.9 billion for local authorities, neither of which provides a significant boost to sustainability and capacity. For local authorities specifically, £1 per week would mean that HRAs would not balance within the 10-year period and would remain in annual deficit, meaning convergence would have limited to no impact on their sustainability in the long-term.

However, the introduction of £2 per week convergence would mean housing associations would have £2.2 billion additional income over 10 years, with local authorities benefitting from £3.1 billion additional income over the same period. £2 per week would have a significant impact upon the financial viability of providers, with improved interest-cover projections for housing associations. As outlined in the Savills analysis (page six of the resume), the estimate from a central scenario with £2 per week convergence, where local authorities reserve 30 per cent for asset management and housing associations reserve 17 per cent, is circa 43,000 new homes against a core plan that provides for relets at formula rent. (This reduces to circa 27,000 or increases to circa 50,000 for £1 and £3 respectively.)

In the case of local authority HRAs, they would be in balance again by 2034/35, albeit with a nearly £5 billion hangover of earlier debt.

These are significant differences between £1 and £2 per week convergence, and we would strongly encourage the government to introduce £2 over £1 per week, from the consultation options. The additional income generated by £2 per week would provide more of the necessary income required to meet rising costs and regulatory requirements across the sector, such as the introduction of Awaab’s Law, the new Decent Homes Standard (DHS), Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES), net zero targets, and building safety (further outlined below).

Additional funding required

However, it is important to note that the introduction of £2 per week rent convergence will not be sufficient to meet government ambitions for both supply and quality and must be accompanied by additional funding for existing homes, or it will not be sustainable. While the quality of existing homes has improved significantly in the past two decades, the amount of money required to meet new and forthcoming regulatory requirements cannot be raised through rents alone.

CIH acknowledges that the government has committed a significant amount of funding for existing homes in the sector to date, including the Warm Homes: Social Housing Fund, the opening of the Building Safety Fund to providers, and the continuation of the Heat Network Transformation Programme. However, in our submission to the recent Spending Review, CIH suggested that a longer-term aim for government should be to consolidate existing funding programmes for improving social homes into a single, multi-year flexible fund. This would effectively be a new Decent Homes Programme, allocated according to need and linked to an updated standard, that can be used to improve quality, safety, and accessibility. It could also include funding for energy efficiency, clean heat, and climate resilience after the conclusion of the Warm Homes: Social Housing Fund later this decade, once the delivery of Wave 3 and a prospective further Wave has been completed. These ideas have further been demonstrated in Southwark Council’s proposal for a new Green and Decent Homes Programme and the National Housing Federation’s proposal for a Social Housing Investment Fund.

In particular, our work on the parallel consultations for the Decent Homes Standard (DHS) and Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES) have indicated that without additional financial support to invest in existing homes alongside these new regulatory requirements, the impact of convergence will be weakened and housing providers’ ability to both expand new supply and upgrade existing homes to the required standards will be constrained. While our analysis and member engagement are ongoing, our discussions to date suggest that the MEES Impact Assessment underestimates the costs of implementing the proposed changes, and is therefore likely to impact the number of new homes that can be delivered. Likewise, the new DHS outlines large-scale, significant changes that the sector is still modelling. Members have told us that the costs to implement the proposals will be high and likely to be beyond the consultation’s Impact Assessment, noting that the previous introduction of the Decent Homes Standard came with funding. Whilst further information on these proposals will be outlined in our consultation responses, it is clear that the scale of changes and high costs associated with implementation will use up more of the additional capacity created by rent convergence than initially expected.

Additionally, there continues to be uncertainty around other policies, which members have highlighted need clarity to determine the level of income required. For example, the costs of introducing the Heat Network Technical Assurance Standards (HNTAS), which aims to improve the quality and efficiency of new and existing heat networks, have been raised as a concern by CIH members and partners. Around two thirds of existing heat networks are owned or operated by social housing providers. Although specific cost estimates are not yet available and subject to the final design of the policy, the cost per home of meeting HNTAS in existing homes across the social housing sector could be significant. This cost would need to be folded into existing asset improvement programmes and could absorb a substantial amount of the rental income providers obtain from convergence.

Other policy considerations

There is further policy uncertainty impacting financial viability which we hope will be addressed in the upcoming Autumn Budget. CIH has consistently outlined the need to restore Local Housing Allowance (LHA) rates to at least the 30th percentile, which is crucial to ensuring that rents remain affordable and sustainable. A member highlighted that their policy of not letting rents go above LHA rates due to affordability concerns is becoming unsustainable, and that rent convergence alone would not have as much impact without unfreezing the LHA rate. There are also further changes such as the September CPI forecast (forecast to be four per cent), which will have an impact upon rent rates and tenant affordability, as well potentially change providers’ financial business planning. We highlight further comments and reforms on the social security system in our response to question 10.

Local authorities in particular continue to maintain a difficult financial outlook, and require additional support, such as rethinking the HRA debt settlement, as CIH has argued for previously. The Securing the Future of Council Housing campaign, led by Southwark Council, outlines these pressures in detail, and the necessary recommendations to ensure the longevity and sustainability of the local authority housing sector. Some local authority members have indicated that the introduction of rent convergence would ‘keep them afloat’, rather than provide any additional capacity or drive forward progress, with the introduction of wider regulatory requirements.

As such, whilst initial estimates on introducing rent convergence were likely to provide significant additionality of new build homes, it now appears that this may be limited, as the Savills analysis demonstrates. Members have already planned for investment in existing homes in their business plans, but these additional and significant costs associated with DHS, MEES, and HNTAS have not been accounted for, and so any additional income will likely need to first be focused on meeting these standards. As members have outlined to us, the development of new homes remains the only major non-regulatory activity which they can scale back to meet other regulatory requirements and avoid further financial, reputational, and other risks, such as being downgraded by the Regulator of Social Housing (RSH).

The sector continues to share the government’s ambition to develop new affordable homes, and the Social and Affordable Homes Programme will help facilitate this, but it is unlikely that additional capacity from rent convergence will be converted to numbers of new homes at the scale required. These trade-offs between existing and new homes are unfortunately necessary for financial viability so that providers can continue to operate effectively for their tenants in existing homes. Without the necessary additional funding for existing homes (as highlighted above), the social housing sector’s contribution to the government’s target of building 1.5 million homes this parliament will be severely restricted, even with the introduction of rent convergence.

In noting this we acknowledge that the government has committed to a wider package of housing finance options in the Spending Review, such as the Housing Bank and private loans. We have welcomed these initiatives, but at this stage it is unclear the scale of the impact these will have.

The case for £2 or £3

Some members have indicated that the previous cap of £2 per week rent convergence was a good balance between provider income needs and tenant affordability. However, this was 25 years ago and there could be an argument that introducing a £3 per week cap would not be unreasonable, given inflation, rising financial pressures, and recent rent policy changes. As the Housing Forum recently outlined, over the last decade, social rents have increased much less than wages, inflation, or private rents, resulting in a 13 per cent real-terms reduction. If they had kept pace with inflation, average social rents would now be £123.73 per week; instead, they stand at £109.44. The abandonment of rent convergence in 2014, followed by four years of rent cuts from 2016–2020, compounded this reduction. While this has eased pressures on tenants — with the proportion of income spent on social rent falling from 29.2 per cent to 26.4 per cent since 2014–15, and those reporting difficulty affording housing costs dropping from 41 per cent to 28 per cent — it has also constrained landlords’ ability to invest in maintaining and improving homes. A rebalanced approach to rent convergence could protect affordability for tenants while restoring the financial capacity needed to deliver safe, high-quality, and sustainable homes.

The Savills analysis examines this case for convergence at £3 per week. We would argue that, if the government does not commit to the additional funding required for existing homes to help support the costs of DHS and MEES, alongside other measures, it would arguably be necessary to introduce a £3 per week convergence level. This would help ensure the sector remained financially viable with the high costs for existing homes, and able to provide tenants safe, decent, and warm homes. Yet, we would note that even this level of convergence may not be sufficient to meet the significant costs of forthcoming policies relating to quality and decency, especially DHS2, MEES, and HNTAS, without an additional existing homes funding stream.

Ultimately, CIH believes that there must be a broader conversation about what rents are for. This is why our call for £2 per week rent convergence must only be implemented alongside additional funding for decency and quality in existing homes, as the current model of CPI plus one per cent no longer covers both the significant investment required of both existing homes, and the additional income to deliver much needed new homes. To truly tackle the housing crisis at its root, rental income will not be enough to cover all areas of investment needed.

In assessing the impact on new supply, the Savills analysis makes assumptions about the proportion of the additional rental income which will be directed towards expenditure on existing homes (asset management). Their base position is that, for convergence at £1 per week, housing associations will retain 25 per cent of additional rental income for existing homes, and local authorities will retain 50 per cent.

At £2 per week, they will retain 17 per cent and 30 per cent respectively, and these amounts would drop to 14 per cent and 26 per cent at £3 per week.

Savills estimate that, on this basis, with convergence at £1 per week, housing associations would have capacity to build between 18,305 and 33,579 additional homes, and local authorities to build 9,214 to 20,672 additional homes, over 10 years in both cases. (The range depends on practices about relets, noted above.)

At £2 per week convergence, the respective figures for housing associations are 25,405 to 40,680 extra homes and for local authorities, 17,764 to 28,310 extra homes. The analysis shows a modest further increase for convergence at £3 per week.

Clearly these figures are projections based on a range of assumptions and are intended to give overall indications of additional capacity at the different rates of convergence.

It is important to note that the benefits and impacts of rent convergence will vary for housing providers, often dramatically. As the Savills analysis indicates, there will be a significant impact of the DHS/MEES proposals upon the ratio between spending of additional rent income between existing homes and developing new homes. Some members have highlighted that they have higher levels of disparity between current rents and formula rent levels, as well as the older age profile of homes impacting upon costs for DHS, MEES, and retrofit. It will also vary based on providers’ priorities, geography, current financial standings, investment plans for existing homes, development plans, and local politics, specifically for local authority members making decisions on rent policy. For example, Table 2 in the consultation shows the regional breakdown of the gap between actual and formula rent, which demonstrates that the North has a much smaller gap than London. Although there will be variation within this for providers, it is clear that different areas of the country will feel the impacts of rent convergence to varying degrees. We would therefore encourage focus on individual providers’ responses to the consultation to highlight where there may be regional or other differences between the benefits and impacts. This may also provide evidence for the case of local flexibility in setting rent convergence, as providers will best know their tenants, stock profile, and local environment.

As stated above in question eight, our members are still determining the costs of parallel government proposals such as DHS and MEES. However, we wanted to provide member case studies (below) of some of the indicative impacts of different levels of convergence, with the caveat that these may not include the impacts of DHS/MEES proposals and these may therefore change. Many members only provided evidence for £2 per week or above, as the £1 per week cap has been clearly expressed to make a limited impact (as outlined in question eight).

Finally, some members have expressed concern over a perceived lack of clarity in the government’s rent policy around the current ability to charge an additional five per cent (or 10 per cent for specific providers) flexibility on top of some formula rent levels. Without the ability to converge to these flexibility levels, some providers have highlighted they could experience limited additional capacity or benefits from the introduction of convergence, compared to current rent levels with this flexibility. We would welcome government clarification on this, and a review on its inclusion in the rent policy, alongside consideration of tenant affordability.

Case studies

A housing association member with 14,000 homes operating in the Midlands and South of England stated that £2 per week convergence would provide £1.5 million a year, and would take six years to reach formula rent (although noted this would not be linear for all tenants). £3 per week would generate an additional £2.2 million a year, and formula rent would be reached in four years.

Another housing association member working across England demonstrated the difficult decisions for providers between existing homes and new build homes. They shared that they could either provide 240 new homes if convergence were to be set at £3 per week, or complete energy efficiency works at 1,240 homes, whilst also replacing 5,125 housing components. This is compared to 150 new homes or energy efficiency works for 750 homes and 3,075 replacement components, for £1 per week convergence.

A further housing association member with tenants across England shared that they could potentially build 490 additional homes with £2 per week convergence, with this increasing to 600 additional homes with £3 per week. However, they expect the additional funding will be used for both new and existing homes, so this is only indicative.

A housing association member working in the North shared that the expected benefit of additional income from £2 per week would be £281,000 in year one, falling to £24,000 in year 10, and for £3 per week it would be £357,000 in year one, falling to £17,000 in year 10. The proposed rent uplifts would apply to circa 20 per cent of their social rent homes, and the additional income would likely need to be spent on existing homes rather than a significant increase in new homes in their upcoming business plan, with a review following changes in the Autumn Budget.

One local authority member in the South of England with 10,000 homes indicated that convergence at £2 per week would provide an additional annual income of £800,000, which was expected to be spent on existing and new build homes.

Finally, a housing association member working in the South East of England shared that they could build 645 additional new homes over 10 years at £2 per week convergence, or 715 over 10 years at £3 per week. This would be a significant increase on their current development programme.

The introduction of rent convergence focuses on the idea of fair rents, and overall principles of fairness, so that those in similar properties in the same area, managed by the same provider, are paying the same level of social rent. For many of our members, there are considerable disparities between rents below formula rent level, which has a significant impact upon their financial viability. Convergence is therefore an important mechanism to ensure financial sustainability for the sector, as well as stabilising rents fairly for similar homes.

However, CIH are very aware that discussions of rent increases are likely to cause anxiety for many tenants, and it is crucial that affordability and tenant voice are key to these decisions. As the professional body for housing, we work in the public interest and in partnership with other organisations to support tenants.

Additional income from rent convergence cannot be assumed to only provide new homes. Although this is in desperate need, providers know that current tenants will expect increased investment in existing homes with increased rents, and new homes will not be a direct benefit to them. As outlined above, it is now likely that a significant proportion of the additional income from rent convergence will be spent on meeting standards with the DHS, MEES, and other requirements, and this will therefore directly ensure that current tenants are living in safe, decent, and warm homes, and benefit from the increased rent levels. However, it is important to note the lack of voice for those in need of these new homes, such as in temporary accommodation or on waiting lists, who will benefit from the development of much needed new social homes.

Wider social security support

Our members have also been clear in their feedback that tenants are at the heart of their work, and they have existing mechanisms in place to support those in financial difficulties. Many said they were undertaking updated impact, equality, and affordability assessments, to determine which tenants may be most impacted by rental increases, and to target support, such as early debt intervention referrals. Yet, as CIH has previously called for, it is vital that there is an adequate and effective social security framework to support people who need it, beyond the support offered by housing providers. Social security provision should be reformed to support those on the lowest incomes, and government should also act to provide long-term price protection to support people in or at risk of fuel poverty with high energy costs. Additional policy changes are necessary to ensure affordability, such as removing the two-child limit, which is the most cost-effective way to reduce child poverty and would lift 300,000 children out of poverty. We hope to see this addressed in the upcoming Autumn Budget.

Finally, we are also aware that there are wider conversations related to welfare benefits, affordability, and rent that must frame this response. Around 30 to 35 per cent of tenants do not receive benefit and will be directly impacted by the increase. But for those in receipt of universal credit (UC) or housing benefit (HB) the whole of the marginal cost is covered, so unless they are affected by the benefit cap, they are no better or worse off. For this group affected by the benefit cap, the only way to improve affordability is to improve the generosity of the benefits system – which is wholly a decision for the Department of Work and Pensions and HM Treasury.

To support this consideration, we have completed a separate piece of analysis alongside this consultation response to outline the impacts on benefits, different tenant groups, and wider affordability concerns. This can be found here. In summary, it shows that most low-income tenants are protected from rent increases through HB and UC. However, affordability pressures fall mainly on households at or just above the upper threshold, families affected by the benefit cap, and, to a lesser extent, those impacted by the bedroom tax. Overall, the number of tenants significantly affected by modest rent increases is likely to be small, but the impact is concentrated within these specific groups so could be addressed.

1 April 2026.

Rent convergence must be implemented immediately with the 10-year rent settlement (from 1 April 2026) in order to be effective. Members have decisively stated that this is needed as soon as possible, and introduction in 2026 would provide much welcomed alignment with the 10-year rent settlement and the new Social and Affordable Homes Programme. To implement rent convergence to a different timeline would be confusing and the delay would be unwarranted.

Further, confirming rent convergence will be introduced in April 2026 is crucial for it to be included in upcoming business plans. A member shared with us that the impact on business plans will be cumulative with convergence, which will make a significant difference. Any delay will reduce the speed and overall impact of rent convergence, as well as limiting financial viability for the sector for a longer time-period. In particular, one member pointed out that new homes take an average of 24 months to complete, and any delays to tackling the financial stability of the sector will delay the government’s target of building 1.5 million homes this parliament.

Since the historical changes and reductions in rent policy, alongside rises in inflation and other costs, the sector has not recovered financially to be able to deliver to its full capacity. This was noted by the RSH in November 2024: “the risks to local authorities’ and private registered providers’ viability have intensified and their financial performance continues to weaken”. Any delay to implementing rent convergence further prolongs these concerns, and slows down progress for both current and future tenants, with less investment in existing and new homes. This need is urgent; as of March 2024, over 1.3 million people were on local authority housing registers waiting to access a suitable social tenancy, with over 10 per cent of those (131,040) living in so-called temporary accommodation, which is highly damaging to households and is estimated to cost councils over £2.3 billion per annum. We must act now to ensure that we fix these issues at the root, by building quality social homes in the right places.

Our members have indicated that rent convergence must be in place for at least 10 years, or for as long as is needed to reach formula rents. This would ensure continued alignment with the long-term rent settlement and the Social and Affordable Homes Programme, providing certainty and stability for the sector. It is important to note that this would also not be a policy which would impact all tenants for the full length of time, as many will reach formula rent relatively quickly.

Our analysis with Savills clearly shows that the income for both housing associations and local authorities will be significantly improved over a 10-year period with £2 per week rent convergence.

Additionally, while the 10-year rent settlement is welcome, there is obvious concern that a change of government might result in a change of policy, as the sector has experienced constant and unpredictable policy change on rental income in recent years. CIH calls for the settlement to be set in legislation, which offers some protection in terms of future changes in policy, making changes more difficult to implement and requiring debate and parliamentary approval.

For more information on the consultation please visit the government's website.

For more information on our response please contact Megan Hinch, policy manager, megan.hinch@cih.org