11 Sept 2025

CIH's response to the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government’s consultation on a reformed Decent Homes Standard for social and privately rented homes

CIH welcomes the opportunity to respond to the consultation on a reformed Decent Homes Standard (DHS) and supports the extension of the standard across social and private rented housing, providing a degree of consistency for tenants. CIH’s previous work contributed to the introduction of the original standard, and we have been pleased to participate in the government’s review, leading to the proposals in the consultation.

The first DHS was developed as a response to decades of underinvestment and consequent poor conditions prevalent across council housing, in particular. It was accompanied by specific funding programmes, ongoing reporting and monitoring, and the development of mechanisms to drive a concentrated focus on improvement (such as the creation of Arms’ Length Management Organisations and Large-Scale Voluntary Transfers to housing associations). Its success can be seen in the lowest rate of non-decent housing now being in the social rented sector, albeit that steps have been necessary through the Social Housing (Regulation) Act, relating to tenant voice, culture, and safety.

Summary

CIH welcomes the government’s proposals for a reformed DHS and supports its extension across social and private rented housing, creating greater consistency for tenants. Overall, we agree with the broad direction of reform, particularly the focus on safety, health, wellbeing and dignity. However, we highlight the need for clearer guidance, realistic cost assessments, and sustained funding to ensure successful delivery.

We have analysed the proposals both in isolation, and in relation to linked government consultations on minimum energy efficiency standards (MEES) and social rent convergence. To inform our view, we have consulted widely with our members and partners across the sector.

Our key points and recommendations are:

- Clarity & alignment: The DHS must sit alongside existing regulations (building safety, fire safety, MEES, Awaab’s Law) with clear, consistent guidance to avoid duplication or confusion.

- Funding & delivery: Costs are significantly underestimated. Government should provide additional funding and establish a long-term decent homes programme to support delivery across all tenures.

- Refinements to standards: We support removing age as a measure of disrepair, adopting more descriptive thresholds, recognising kitchens and bathrooms as key components, and treating ventilation, lifts and communal areas as essential to safety and wellbeing.

- Resident dignity: The standard should prevent trade-offs between essential elements, strengthen measures on damp and mould, embed resident voice to tackle stigma and improve accountability, and allow time to explore practical approaches to incorporating floor coverings.

- Implementation: A phased approach is needed, with priority given to core health and safety issues such as damp and mould, kitchens/bathrooms, and heating. We support a target of full implementation by 2035, with interim milestones.

- Temporary and supported housing: The DHS should apply consistently to temporary accommodation and supported housing, but resourcing and funding challenges must be addressed to avoid negative impacts on supply.

- Private rented sector: Strong enforcement and guidance will be vital given the sector’s diversity and cost pressures. Government should consider tailored support for smaller landlords and ensure consistency with hazard-based enforcement.

- Future resilience: Guidance should incorporate accessibility, furniture provision, and climate adaptation (overheating, flooding, resilience) to ensure homes are fit for the future.

In summary, CIH strongly supports the principle of an updated DHS but emphasises that its success depends on adequate funding, clear guidance, and a cultural shift towards prevention, resident engagement, and long-term investment in existing homes.

Yes – with caution.

We have previously been clear that whilst age can provide a helpful trigger to check the condition of a building component, it may not always be the most suitable guide to understand how that component is performing. We have also argued that what matters most is whether that component is working safely and effectively, which depends on more than its age. Reliance on age can lead to inefficient or premature replacements, rather than good asset decisions rooted in actual condition.

CIH therefore supports a move away from age as a strict test for disrepair as there is growing recognition that a condition-focused and preventative approach is more effective. For example, both the Housing Ombudsman’s Spotlight reports and The Better Social Housing Review (2022) called for a culture shift towards planned maintenance and stronger accountability to residents.

We also know from the BRE’s Cost of Poor Housing report that poor condition, not necessarily age, drives the most serious negative outcomes and, as the consultation itself notes, the report estimates the cost to the NHS of treating health impacts from poor housing at around £1.4 billion per year. Furthermore, research such as The Value of Housing by the UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (2025) reinforces that housing quality is fundamental to people’s health, dignity and wellbeing.

Whilst a home isn’t decent just because components are under a certain age, we recognise that for some landlords, age can still play a helpful role in understanding which components need checking, and planning replacement programmes accordingly. Age could therefore be used as a prompt for investigation, as opposed to a hard line for disrepair.

So CIH supports removing age from the formal definition of disrepair in Criterion B of the updated standard. But we think it must be replaced with a clear, robust framework for assessing conditions. Without that, there is a risk that investment could be delayed until components fail, which would then undermine the preventative intent behind the standard and Awaab’s Law.

Landlords will need practical guidance to support this shift, and we would welcome the opportunity to support the development of this guidance. For example, indicative lifespans for some major components could be used as part of a wider strategic risk-based approach.

Yes – with caution.

Overall, CIH supports a move towards more descriptive measures; this approach would offer greater clarity and transparency and enable residents to be clear about what to expect in their homes. Arguably, it would also bring the standard closer to the way in which residents experience their homes in their daily lives, beyond a focus on technical failure points and moving towards a standard that focuses on usability and safety.

We would draw on the Welsh Housing Quality Standard 2023, as a practical example here. We believe this is a helpful approach that considers how components function in residents' daily lives. It also covers the lived experiences of elements such as ventilation, natural light and digital connectivity, which helps demonstrate that decency standards need to go beyond a compliance checklist, to understand how decency affects residents' everyday lives.

The approach in Wales also reflects the growing focus across Europe that decency standards incorporate dignity, wellbeing and inclusion, which is seen in both the European Parliament’s 2021 resolution on the right to adequate housing, alongside Housing Europe’s 2024 manifesto. Both highlight that housing quality must be judged on habitability, safety, and lived impact which reflects our wider work in this area with the National Housing Federation through the Better Social Housing Review.

We have previously called for more clarity in terms of how the standards are both understood and applied. We suggest that descriptive thresholds can help landlords make more consistent, resident-focused decisions, reducing reliance on rigid pass/fail tests that can delay action. As we noted in our previous decency consultation responses, more qualitative definitions support dignity, and better align asset management with how homes are lived in. They also reduce the risk of 'waiting for failure.' That said, descriptive standards must come with clear guidance and sit within a wider framework of proactive inspection, resident engagement, and accountability — otherwise, flexibility risks becoming inconsistency.

Yes – we agree.

We have previously argued that the current thresholds are set too high and risk masking serious issues until they reach a crisis point. Spotlight reports from the Housing Ombudsman into repairs and damp and mould clearly demonstrate how what can be perceived as ‘minor’ concerns can quickly escalate into much bigger hazards.

The principle that one issue can make a home unsafe is what underpins the current Housing Health and Safety Rating System. This approach is also aligned with wider new regulations, such as the Hazards in Social Housing Regulations, which are designed to help both prevent and minimise risk through better intervention and prevention. This is supported by wider research that shows that disrepair issues not only contribute to physical risks but also to broader issues of wellbeing.

Therefore, we support lowering the threshold to reduce the number of components required to trigger action. We believe this would help align the standard with how risks develop in practice and how residents experience them in their homes, moving the sector towards a more preventative, resident-focused approach to disrepair and decency.

Yes.

We support the concept that functioning kitchens and bathrooms are key, as they are fundamental to everyday life. The impact of living without a functional bathroom or kitchen for residents is both very immediate but also personal and it would not only affect a household on a practical level but also intersect with residents’ health, wellbeing and dignity. For comparison, the Welsh Housing Quality Standard recognises kitchens and bathrooms as key components of a safe, functional and decent home. Wider research supports this, with poor quality kitchens or bathrooms being linked to negative impacts on health, hygiene and wellbeing. Therefore, we strongly support the proposal to classify kitchens and bathrooms as key components; their failure or absence cannot be ‘offset’ by repairs or good conditions elsewhere in their home. Therefore, failure in either should be considered sufficient to fail the standard, which reflects the clear evidence of the essential role that these spaces play in residents' daily lives.

Yes.

We support the principle of having a clear, comprehensive list; this makes the standard fairer and easier to enforce. However, we believe there are some gaps that need addressing to ensure the list reflects residents lived experiences.

Firstly, we believe that the issue of ventilation must be made clear, as the health risks arising from damp and mould are well known but still occurring. Therefore, due to the link between ventilation and these risks, residents should be able to expect that this be treated as essential repairs, rather than optional. This is in line with the direction of travel from Awaab’s Law, which establishes timescales within which action must be taken by landlords in response to reports of damp and mould.

The consideration of the importance of communal and shared spaces is particularly relevant in the context of high-rise living. Spaces such as lifts, stairwells and shared spaces are often central to ensuring residents have safe and equal access to their homes. Wider research on human-centred housing design supports this and highlights communal spaces as central for accessibility, but also for social interaction, inclusion and well-being. Arguably, this extends to external components such as bin stores, paths and boundary walls; the disrepair of such components can have direct consequences on residents' health, safety and wellbeing.

However, we understand that any components list should seek to avoid duplication with existing legislation or regulation, especially those on building and fire safety. Also, where a component does not exist by design, especially in older stock, the absence would not automatically count as a failure.

We believe that a clear and comprehensive list would enable the standard to better align with the way residents live their lives and what they expect from a decent and safe home.

Yes, with conditions.

A tiered list can help focus effort, but the split must not harden into a hierarchy that ignores risk. In practice, some items placed in “other” — door entry, rainwater goods, external lighting, pathways and steps — can have major consequences for safety, access and dignity when they fail. When a component poses a clear health or safeguarding risk, it should be treated with the urgency of a “key” failure, regardless of the label. Two regulatory changes support this. Firstly, the consumer standards expect landlords to understand and fulfil maintenance responsibilities including communal areas, and to deliver equitable outcomes, which requires judging the real-world impact on the household, not just the component’s category. Secondly, the direction of travel under Awaab’s Law is towards earlier, preventive action where there is risk of harm.

We welcome the proposed additions. In particular, we argue that ventilation is key in addressing issues around damp and mould, and lifts are essential in terms of safety, accessibility and inclusion. We have previously drawn on evidence that demonstrates how these elements are central to resident health and well-being, and the importance of tackling seemingly 'smaller' issues before they escalate.

We believe this supports research that evidences how housing quality and decency are strongly related to resident health, dignity and wellbeing, therefore supporting an approach that a decency standard needs to reflect lived experiences, not just a technical understanding of a 'pass' or 'fail'

In summary, we believe that the standard should retain the 'key/other' structure but have a degree of flexibility in how those rules are applied, to account for the severity of the issue; the likelihood of harm; and the interaction with any known vulnerabilities in the household, so that the standard accounts for the realities of residents’ lives.

In our previous responses, we have been clear about the importance of additional elements as an essential part of both housing quality and residents' lives. Elements such as lighting, bin stores and shared spaces have a direct impact on residents' health, safety and dignity and therefore should not be considered as supplementary components.

However, we also recognise the practical and legal complexities in terms of ownership and duties for such components and spaces in the private rented sector. We do not feel that this complexity should mean a lesser quality of decency for private residents. We believe that all landlords should have greater responsibility for ensuring all elements of a home are safe, decent and fit for residents' everyday lives.

Social landlords should be expected to maintain such components as part of their core duties; however, we also believe that, to drive standards across all tenures, private landlords should now have a clearer requirement to take responsibility. This should be, in particular, in relation to communal and shared spaces linked to buildings in private ownership. The government should provide clearer guidance on how responsibilities should be allocated in mixed ownership settings to ensure accountability and decency for all residents.

CIH believes that government and the sector must consider how the revised standard works with and alongside wider regulation and legislation. The Decent Homes Standard has the potential to be the main framework under which other regulations sit. Currently, landlords are juggling various requirements — energy standards, building safety rules, consumer regulation — which do not always join up. If the Decent Homes Standard becomes the foundation, it could bring other requirements together and make the system easier to follow for landlords and clearer for residents.

But the standard on its own won’t be enough. The guidance that sits alongside it is where the real difference will be made. Done well, this could provide landlords with clear, practical advice on how to meet the standard in different situations, especially in mixed-tenure buildings where responsibilities are often blurred. It is also a chance to bring residents into the process and make sure their lived experience shapes how the rules are applied.

In Wales, the government has produced detailed guidance to support their housing quality standard, and landlords have found that really useful in practice. We think England should follow that approach, and CIH would be keen to play a role in helping government design and test this guidance with landlords and residents.

No, we believe that all are important to decency, but we acknowledge the definition of shared space needs to be considered (for example if referring to communal space within a flatted block or external shared space).

Whilst we support the aim to define minimum standards around clear and core components, we have concerns that picking three from the four could result in inconsistency with respect to the decency standard. It risks residents being asked to accept ‘trade-offs’ where they are expected to live with disrepair in one key area because of a repair to another. We do not believe that some elements of the home are interchangeable, but each has a key role to play in what makes a home safe and decent.

As explored above, kitchen hazards can lead to further costs and risks concerning health and safety. Also, wider research has clearly demonstrated the integral role that noise can play in terms of a safe, healthy and decent home. Shared and communal areas are strongly linked to safe, inclusive and accessible homes. Therefore, this needs to be managed carefully as the ‘three out of four’ approach could risk undermining fairness and could even weaken the enforceability of the standard.

We believe that there is strong and compelling evidence to be very clear that kitchens, bathrooms and noise insulation should be approached as non-negotiables due to their direct links to wider health, safety and decency risks. We would argue that communal areas are important, particularly in flatted blocks etc, but more broadly may need to be understood on a case-by-case basis, where the definition is taken more broadly. The absence of a functioning kitchen, bathroom, or sound insulation has more immediate implications for health and habitability, so we believe that clear definitions and guidance are required in relation to shared spaces in this context.

Yes.

We believe that there would be a real compromise to the way in which the decency standard could be applied. This could result in inconsistency and unfairness across differing landlords and property types, meaning residents could have very different levels of protection under the standard.

We are also concerned that the regulation of the standard may be more complex if it is based on choices with a wider level of variation and may encourage the prioritisation of elements with lower costs, especially in the context of constrained resources. We believe that both could result in situations where residents are asked to choose between what are essential elements of any safe and decent home, and whilst unlikely to become standard, could be interpreted to allow unfair ‘trade-offs’ in practice.

This all goes against the aim of the standard to support a broader concept of what a safe, healthy home is.

To ensure that the standard is consistent and fair for all residents CIH recommends that:

- Functioning kitchens, bathrooms and noise insulation are considered as core requirements.

- Communal areas are considered in context, particularly in high rise, supported or specialist accommodation.

- Guidance is developed with the sector, and residents, to understand how these features work in practice, making the standard easier to understand, implement and regulate.

An international approach underlines our points here; the UN’s definition of adequate housing stresses habitability, accessibility, and cultural adequacy. All four facilities proposed in Criterion C support these dimensions. Omitting any of them without clear justification risks undermining tenants’ ability to live with dignity.

The importance of window safety has been underlined by the recent report from the Housing Ombudsman. This revealed problems in key areas, including delaying repairs to pick up through programmed works, and poor communication with tenants

We are aware that many landlords already install window restrictors where there is a risk of falls from height, and support this being a requirement. Tenants should be made aware of how to override where possible, but of the risks inherent in doing so. Consideration should also be given on how to support older and / or disabled people to manage window restrictors.

Yes, with caveat. Although there is a requirement to ensure homes are free from the hazard of entry by intruders, the perception that they are safe within their home is significant to the wellbeing of residents and warrants additional consideration, particularly where residents may indicate feelings of vulnerability, insecurity or other risks.

Yes, it should be an option for landlords, but there should be a common threshold required for compliance, set out in guidance to be clear for landlords and residents.

Additional home security measures should be considered as part of planned programmes of improvement unless there is a clear requirement to act more quickly in response to significant risks to residents.

We agree that floor coverings are an important component of a decent home and should be required in circumstances where there is need and agreement with the tenant.

However, we recognise that this is potentially a complex issue due to:

- Cost implications: In all our engagement this has been raised as having significant costs attached, in excess of those estimated in the impact assessment, which will have a knock-on effect on other investment needs by landlords.

- Tenants’ preferences: Not all tenants will want landlords to provide floor coverings if this limits their own choice and control over their home.

- Targeted support: Many landlords have funds or links to charitable foundations that can support tenants where they are lacking basics in terms of floor and window coverings and furniture.

Evidence has demonstrated that a lack of adequate flooring can impact safety and dignity for residents in both social and private housing. End Furniture Poverty (EFP) has shown that whilst flooring is considered by many residents as an essential element of any home, 1.2 million people across the UK still live without flooring, 61 per cent of whom are social housing tenants. Other studies show this is a large-scale issue, for example, research in 2024 found that only one in ten social landlords provide flooring beyond kitchens and bathrooms, and 42 per cent provide none at all. Resident lead research demonstrates the cost to residents, not only in terms of finance. Many (45 per cent) without flooring had to spend in excess of £1,000 to put it in themselves. This research also evidences the wider costs; a lack of flooring can create safety issues, experiences of shame, embarrassment and discomfort.

It is worth noting that the Welsh Housing Quality Standard now requires flooring in all habitable rooms. Solutions across the UK already exist with providers addressing these issues, for example, Thirteen Group’s pilot of an improved empty homes standard, which included flooring and decoration, didn’t just raise satisfaction; it also reduced arrears, repairs and re-let costs, making it close to cost neutral.

However, CIH recognises the complexities of such an approach, both in terms of cost and delivery. Whilst we agree with the principle that a reformed DHS should include a requirement to ensure all homes are safe and warm, we believe that the government should work with landlords to develop practical approaches, learning from pilots like Thirteen’s, so that this can be delivered fairly and sustainably.

We believe that a ‘test and learn’ or pathfinder phase, similar to that being adopted in the phased implementation of Awaab’s Law, could be developed to explore how to ensure that the implementation of floor coverings is achievable and effective. For that reason, we support the NHF’s proposal that government, sector bodies and volunteer landlords should explore the issues and greater understanding of when and how to implement this proposal, and the level of funding required, to be included as part of the DHS once this is established.

CIH agrees with updating the heating requirement in Criterion D to require a system sufficient to provide heat to the whole home. We have two further points to add for consideration:

- Households facing unaffordable energy costs may ration their heating to keep their bills manageable, or to avoid falling into energy debt. One of the ways this occurs is through a practice sometimes called ‘spatial shrink’, or heating only one room in the home and staying in that room as much as possible. This has a negative impact on the fabric of the home, can create an unhealthy living environment, and has been shown to have links to mental ill-health. Government should consider whether a requirement for the provision of heat to the whole home could make the practice of ‘spatial shrink’ more difficult and/or expensive for households to undertake, especially if radiators in different rooms are not programmable or controllable to be turned on and off individually. If this occurs, households may turn the heating system off in its entirety and use a secondary heating appliance to warm one room of the home. We think this could be addressed in guidance, rather than through the Standard itself, and highlight good practice approaches such as ensuring Manual or Thermostatic Radiator Valves are in place to ensure room temperatures can be controlled.

- Consideration needs to be given to innovative building design types that do not require a conventional heating system to maintain safe indoor temperatures, especially PassivHaus and some homes retrofitted to EnerPHit standards. The original Criterion D acknowledged that types of heating without a distribution system as such (i.e. storage heaters) are acceptable. However, PassivHaus developments often only contain Mechanical Ventilation with a Heat Recovery system (MVHR) to maintain thermal comfort, and these systems tend only to be required when the outdoor temperature is very low. Instead, PassivHaus homes use rigorous design standards to minimise the energy demand of the home and retain a sufficient amount of ambient heat (e.g. from occupants, and from solar gain) to maintain safe indoor temperatures. Government should take this opportunity to update the wording of Criterion D to reflect PassivHaus design principles.

We strongly support a zero-tolerance approach to damp and mould that causes, or has the potential to cause, detriment to a resident’s health, safety, or wellbeing. All homes contain some level of moisture, but the threshold must be whether this translates into a risk or impacts on people’s lives. BRE research (2021) shows that Category 1 damp and mould hazards are among the most damaging housing conditions, with long-term societal costs of £4.8bn over 30 years.

We also recognise that some level of moisture is a natural feature of all homes, but the Decent Homes Standard must make clear that any damp and mould which undermines residents’ health, wellbeing, or habitability is unacceptable. Landlords should therefore be required to identify, prevent, and remediate harmful damp and mould proactively, with clear accountability for meeting this standard.

Research has highlighted that the lived experience of damp and mould has direct impacts on not only physical health, but also wellbeing, with residents reporting stress, embarrassment and isolation as well as health concerns. Evidence has also found that investment to address hazards such as damp and mould leads to tangible improvements in residents’ health and wellbeing, as well as satisfaction with their landlord and a reduction in long term costs.

The Housing Ombudsman’s Spotlight reports and casework show that damp and mould have too often been dismissed as “lifestyle issues” rather than recognised as serious problems that demand urgent action. CIH is clear that this is connected to wider work needed to address a shift in culture, moving away from blame, and evolving into more proactive approaches in dealing with damp and mould.

As the professional body for housing, CIH’s role is to help landlords make this shift in ways that are fair for residents but also achievable for providers. That means sharing good

practice, drawing on evidence of what makes a difference, and making sure that ambition in policy is backed up by realistic investment and delivery.

Yes.

CIH believes that this is the most appropriate approach. The standard needs to be clear on the basic expectation of a baseline of homes free from damp and mould, whilst Awaab’s Law provides a regulatory safety net should the severity and risk of harm increase. However, it is also clear that the two pieces of policy must work together, especially if we want to move towards a more proactive approach to dealing with damp and mould.

Damp and mould have significant health risks as well as much wider socio-economic costs to society. Even at relatively low levels we know that poor air quality contributes to health risks, particularly for children, and those with additional vulnerabilities. Research has shown that in addition to the health risks, residents also often experience high levels of stress, stigma and a loss of confidence, especially when problems are unresolved.

Setting Criterion E within the Decent Homes Standard makes it clear that a preventative approach is expected of landlords, whilst Awaab’s Law provides a regulatory function for when it could be considered a hazard or cause harm. This then creates a united and consistent framework to encourage preventative action whilst ensuring residents have a clear route to redress if this action is not taken quickly enough.

This clarity around preventative and responsive work is going to be central to rebuilding resident trust around this issue. It also reflects the wider evidence that clearly demonstrates that approaches to design, ventilation and insulation need to come together if we are to tackle damp and mould on a much larger scale in the future.

Yes, but with an important caveat. We strongly support treating Category 1 damp and mould hazards as a clear failure of the standard. In previous responses we have referenced a wide range of evidence. Category 1 hazards relating to damp and mould have the most harmful risk to residents, linked to wider issues with health complications and costs.

However, it is important to note that the impact on residents' lives can, and does, start well before the Category 1 threshold. Ongoing issues with damp and mould may not trigger a Category 1 response but can still negatively impact the quality of life. The evidence is clear on the impact this can have for a wide range of health and well-being issues. So, whilst Category 1 hazards are a clear failure of the standard, the framework should also be part of a more preventative approach in line with the proactive aims behind Awaab’s Law.

Yes. We would highlight three further points:

- Culture and stigma: This is an important issue that extends beyond damp and mould. However, the evidence of how damp and mould occurrences have too readily been attributed to ‘lifestyle’ highlights how stigmatising social housing residents shifts responsibility away from landlords. We have been clear that the sector’s approach to its services needs to be more inclusive and fair to all residents. Work with respect to decency needs to consider the impact that the entrenched stigmatisation of residents has on decisions made about their homes and repairs. Changing this means landlords need to treat reports seriously, invest in training, and build a culture where residents are listened to and supported. The requirements under the forthcoming Competence and Conduct Standard should support this.

- Resident voice and co-production: As a way to tackle such stigma, it should be more widely recognised that residents know the reality of living in their homes and need to be involved in the identification of issues and solutions. Approaches designed with and for residents can be a practical way to build stronger organisational cultures, but also to stop problems from escalating in the longer term.

- Design and long-term investment: We also need to think longer-term with respect to design. UCL’s Healthy homes for all is an important piece of work that shows how poor insulation, ventilation, and unsuitable materials add to damp and mould risks, with wider health costs and implications. This is also an opportunity to utilise DHS as a framework into which work around warmth, energy efficiency and safety can be brought together more consistently so that homes are more sustainable and resilient.

These additional points highlight that ensuring homes are decent takes us beyond compliance into the culture of organisations and the ways they work with, listen and respond to tenants. This matters not only for residents’ health, but also for dignity, trust, and the relationship between landlords and the people they house. CIH will continue to support the sector on this through its work on professionalising the sector, with good practice and guidance.

Yes.

Currently, the second proposal is unclear as to whether it means that where Criterion C cannot be met in full (i.e., in terms of cooking facilities as described), the accommodation must meet all the other requirements of Criterion C (i.e., windows, home security measures and floor coverings) or instead meet the other criteria of the standard in full. We would recommend that the former be made explicit so that the remaining elements of Criterion C are expected and enforceable in all types of temporary accommodation (TA).

As stated in the consultation document, all TA is currently expected to meet Criterion A. However, there is no reliable data on the conditions of TA, and there is no official reporting mechanism to ensure that these standards are being met. Additionally, there is no requirement or consistent pattern of inspection of TA nationally before a household’s placement, meaning that local authorities can’t demonstrate their suitability, as per their statutory duty. The concern is that if local authorities cannot currently meet (or aren’t required to evidence that they meet) their responsibility to ensure TA meets Criterion A, then they will have difficulty in assessing and enforcing compliance across the remaining criteria.

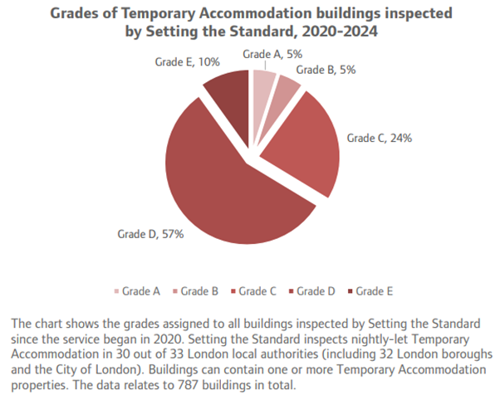

Some councils, such as Islington and Slough already require TA to meet the DHS. However, where inspection regimes have been put in place, the evidence suggests a high level of disrepair in TA. Setting the Standard: an optional pan-London temporary accommodation standards and inspection regime, run by the Commissioning Alliance, found that two-thirds (67 per cent) of nightly paid accommodation inspected between 2020 and 2024 did not meet a ‘Grade A-C’ against their standards and so failed inspection.

Any review of compliance with the DHS in TA is likely to uncover many properties in need of improvement. Local authorities will need to be resourced adequately to work with providers to improve these conditions, and enforce compliance.

Yes.

There is evidence that, even without regulated standards for TA, some private providers withdraw units and raise prices at will, knowing that there is a chronic lack of supply of affordable housing and TA enabling substantial profits to be made. This situation leads to local authorities often being forced to make the ‘least worst’ options to house homeless households. In other circumstances, to protect supply and negotiate more favourable leasing agreements, some local authorities have funded the improvement of TA. It is important that landlords be held to account for substandard accommodation and that meeting the DHS is a prerequisite, evidenced via official reporting and inspections, prior to households being placed in any TA.

To avoid unscrupulous landlords exploiting any regulatory gaps between tenures, the timelines for the application of the DHS should be implemented concurrently across rented homes and TA. To that end, we recommend that the DHS also be extended to asylum accommodation provided by the Home Office to rule out the morphing of practices already found in both TA and exempt accommodation to gain better returns from the public purse in the least burdensome way.

Regarding local authority or housing association-owned properties, a further concern to highlight is the potential for the implementation of the DHS to result in a net loss of social housing. This may be where regeneration blocks used as TA are no longer suitable due to the cost of compliance, or where housing associations have given local authorities first refusal over disposal stock due to the cost of modernisation. If these units can no longer be used as TA, it is important for the government to support registered providers retaining social housing stock.

We support the implementation of the DHS to the supported housing sector and await the government’s comment on the sector’s response to its regulatory proposals. The core challenge in applying the DHS across this sector is the risk that undertaking these works, alongside the other expectations of the Supported Housing (Regulatory Oversight) Act, could be a tipping point for the viability of many schemes and lead to providers exiting the market entirely. These warning are not hyperbole; in 2024, the National Housing Federation (NHF) surveyed members, finding that 1 in 3 supported housing providers would have to close or reduce services in the future, and pressures have been exacerbated since then. This environment is compounded by the demise of the Supporting People programme in 2009, short-term commissioning cycles, and increasing operational costs.

In our submission to the HCLG committee in 2022, we argued that the continued absence of a long-term funding settlement for supported housing is the most significant cause of poor conditions and a barrier to improving them. Without investment, many good providers will be incapable of viably meeting the DHS.

Yes – with caveats.

We welcome the proposal to provide local authorities with flexibility to serve enforcement notices on the person or organisation most responsible for a DHS failure (whether the immediate leaseholder landlord, a superior landlord, or the freeholder). This is essential to ensure the standard is enforceable in complex ownership arrangements.

However, we would highlight several risks:

- Complexity and capacity for local authorities: Determining liability through leases, head leases, and superior landlord arrangements can be legally complex and resource intensive. Councils will require clear statutory guidance and potentially access to additional expertise to avoid lengthy disputes.

- Risk of enforcement delay: Where disputes arise about responsibility, tenants could face prolonged periods in substandard housing. A “joint and several liability” approach could be considered, allowing councils to act against whichever party is most able to remedy the issue, while they determine ultimate responsibility.

- Leaseholder consent requirements: Where leaseholder landlords need superior landlord consent for works, there is a risk of delay or refusal. Guidance will need to make clear how local authorities should approach these cases to avoid unfairly penalising leaseholder landlords who have taken all reasonable steps.

Potential chilling effect in the PRS: Some leaseholder landlords may exit the sector if they feel they are being held responsible for matters outside their control (e.g. building fabric failures), reducing PRS supply. A proportionate and transparent approach will be essential.

Yes – in some circumstances.

We broadly agree that most obligations under the DHS should not generate new costs for leaseholders, as freeholders are already expected to maintain common parts under existing lease terms. However, we foresee certain risks where new costs could arise, particularly in mixed-tenure blocks:

- Communal areas and building components: Proposals to bring rainwater goods, lifts, stairways, entry systems and (in the SRS) external areas explicitly into scope could generate additional major works costs, even if freeholders should already maintain these. Leaseholders may face higher service charges, particularly if works are triggered sooner or to a higher specification than previously expected.

- Thermal comfort improvements: Updates to thermal comfort requirements could require social landlords to carry out building-wide upgrades (e.g. insulation, heating system improvements) that increase costs to leaseholders in mixed-tenure blocks, where they may have limited influence on decision-making.

- Redefined failure criteria for core facilities: By lowering the threshold (from lacking 3 of 6 to lacking 2 of 4 facilities), some blocks may fail the DHS where previously they did not. This could trigger major communal works with cost implications.

- Section 20 consultation risks: While Section 20 processes provide a mechanism for consultation, there remains concern that leaseholders often feel costs are excessive or imposed without sufficient accountability. Proposals to improve transparency are welcome, but robust enforcement of reasonableness will be needed.

In practice, many of these costs may be works that freeholders should already be undertaking, but the DHS may accelerate or formalise obligations, creating new financial burdens for resident leaseholders. We therefore support:

- Clear statutory guidance to local authorities on taking a proportionate approach to enforcement where costs to resident leaseholders would be significant.

- Greater transparency and scrutiny mechanisms for major works, particularly where leaseholders contribute alongside social landlords.

- Ensuring that improvements mandated under the DHS align with leaseholders’ rights under their lease, to avoid legal challenge.

There is merit in guidance for all the additional elements identified in the consultation document. However, we focus here in particular on those with the most immediate impact for existing residents and the increasingly pressing issue of climate change, which carries significant impacts for health and wellbeing:

- Accessibility

- Adaptations to climate change

- Furniture provision.

Accessibility:

A fundamental measure of a decent home is one that supports residents to live and undertake actions of daily living safely and with dignity. For many people who have long-term limiting conditions or disabilities, particularly in rented housing, this is not always possible, and the control they have over their home environment to make it more accessible is limited.

However, research by the Equalities and Human Rights Commission in 2018 revealed that one in three disabled people in private rented housing lived in unsuitable accommodation compared to one in five in social rented homes, and one in seven in the owner-occupied sector. A report by the Levelling up, housing and communities committee, focused on disabled people and the housing sector, highlighted the huge impact of unsuitable housing on disabled people, affecting their dignity, health and wellbeing due to long waits for accessible homes and / or adaptations.

The government’s investment in disabled facilities grants of £625 million in 2024-25 as part of the Better Care Fund, reflects recognition of the level of need but also the cost effectiveness of installing adaptations to reduce the risks to health and demands on NHS services (particularly from falls, estimated at £435 million).

According to the English Housing Survey home adaptations report 2019-20, the most common adaptations required are grab rails in kitchens and bathrooms (42 per cent) and in other areas in the home (36 percent). There are existing guides developed by sector bodies on how to assess and install adaptations in the social housing sector (such as Adaptations without delay, 2019). The NRLA have also provided guidance for private landlords on why and how to support tenants to apply for DFGs for adaptions (Adapting the private rented sector, 2021).

The government could usefully provide guidance for landlords that draws on these existing tools, on how to assess their residents’ needs for adaptation and, where possible, incorporate these into planned works to meet the DHS, to minimise upheaval for residents, and to coordinate and limit additional costs for themselves. It is important to acknowledge that adaptations need to be tailored to the residents and the home to find the appropriate solution.

Adaptations to climate change:

CIH strongly supports and welcomes the prospective inclusion of guidance on climate change adaptations. Over the last year, we have worked with members, partners, and academics to develop a programme of research on climate resilience, especially overheating. References to this work are provided at the end of our answer to this question.

Overall, the evidence strongly supports the need for climate adaptation measures to be retrofitted into rented homes. This has been recommended previously. For example, in its landmark 2019 report on the future of UK housing, the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) included as a priority recommendation that the UK’s 29 million homes needed to be made low-carbon, low-energy, and resilient to a changing climate.

In its most recent report to Parliament on climate adaptation, the CCC repeated that an increasing number of homes will be at risk from climate impacts. Despite this, retrofitting climate adaptation measures such as shutters, ventilation, tree planting, and reflective paint to prevent overheating, or reinforced doors, self-closing airbricks, or sustainable drainage systems to reduce flood risks, have not been treated as a priority.

In previous years, it might have been possible to argue that this was of secondary importance to improving overall decency, installing low-carbon heating, and retrofitting insulation measures, but the extent of the planet’s warming and our growing understanding of its impact on health and housing means we now need to place climate adaptation on an equal footing to other priorities. While climate projections carry an inherent degree of uncertainty, the likelihood of limiting warming to 1.5°C, as per the Paris Agreement, is becoming vanishingly small. According to the UN Environment Programme, there remains a large possibility that eventual global warming will exceed 2°C or even 3°C, a possibility that some climate scientists now believe to be inevitable. At the most pessimistic end of the different global warming scenarios, the extreme climate events we currently think of as rare (such as heatwaves and flood events) will inexorably become the norm.

This will lead, and is already leading, to greater risks to domestic homes. Research undertaken by the Universities of East London and Bath, in collaboration with CIH, has shown that the prevalence of indoor overheating reported in UK dwellings has increased from 20 per cent in 2011 to 82 per cent in 2022. There is significant evidence that overheating exacerbates risks to health and wellbeing, especially for very young and older people, when indoor temperatures exceed 25°C. If temperatures continue to increase globally, by 2050 heat-related deaths in the UK could rise several times over to exceed 10,000 in an average year, especially among vulnerable groups such as older and disabled people. Beyond heat, approximately 6.3 million UK homes are at risk of flooding, a number that will rise to 8 million in 2050 on current climate trajectories. Research shows that flood-induced evacuation and displacement, particularly without warning, increases the risk of anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder. Wind and driven rain will also increasingly affect homes across the western and southern coastlines of the UK, making them more vulnerable to rapid heat loss and serious fabric problems.

Overall, we therefore think the evidence for including guidance on adaptations to climate change within the new Decent Homes Standard is necessary and timely.

In the context of Criterion D and MEES, we would also add that guidance is required on the use of PAS2035 to mitigate unintended climate-related risks during the retrofit process. PAS2035 is the official standard for whole-house retrofit, and specifies how retrofit projects should be managed and delivered. Compliance with it is rightly a requirement of all current government funded retrofit schemes. PAS2035 covers climate risks, especially overheating, in several places. The Retrofit Assessor role is required to consider “additional information that might have an impact on the retrofit project now and in the future”, including “climate change-induced environmental risks, such as increased flooding, extreme weather conditions, overheating and increased relative humidity.” Retrofit designs are meant to include measures to prevent overheating, in accordance with several allied documents, especially the methodology for the assessment of overheating risk in homes, published by the Chartered Institute of Building Services Engineers (CIBSE). A list of measures, such as means of reducing internal heat loads and limiting solar gain, is also included, as is a stipulation to provide advice to the occupant about potential overheating risk.

In theory, PAS2035 is a comprehensive guide to minimising unintended climate risks during retrofit design and delivery. In practice, there is no evidence of whether homes retrofitted in compliance with it are sufficiently resilient to extreme climate events, especially those associated with warming scenarios of 2°C or higher. CIH has previously received feedback from our members that the twin priorities of retaining heat in winter and cooling in summer can be hard to balance in retrofit work, and that focusing on heat demand can inadvertently exacerbate overheating issues in some homes that receive energy efficiency upgrades. In addition, the government has stated in its MEES consultation for the social housing sector that it will only ‘encourage’ the use of PAS in retrofit work. TrustMark has observed that “the percentage of work currently undertaken under PAS2035 relates predominately to [government] funded schemes and is a small percentage of all the work carried out in properties across the UK.” This suggests that encouragement will not be sufficient to ensure PAS is used in retrofit work undertaken outside of government funded schemes, especially in the private rented sector.

Alongside guidance on adapting to climate change, we therefore feel guidance is required to ensure work undertaken to meet the Decent Homes Standard does not unintentionally exacerbate climate risks, especially overheating and increased relative humidity. Overall, guidance should stress the necessity of PAS2035 and allied CIBSE standards, especially for complex work involving insulation, and emphasise that the climate-related aspects of them are not optional if retrofit is to be undertaken safely.

Long-term, CIH is of the view that the inclusion of a new Criterion on climate resilience in the Decent Homes Standard may be required, especially if warming scenarios of 2°C or higher occur. Previously, we have suggested that this Criterion could stipulate that a home cannot be decent unless a) it has a ‘climate resilience audit’ carried out, and b) it has been subsequently upgraded with all recommended measures to meet a reasonable definition of being climate resilient. The audit could be linked to an updated EPC framework, holistically consider the climate risks for an individual home, and make recommendations

on the measures needed to adapt to and mitigate those risks. Eventually, such an audit could be mainstreamed into stock condition surveys, just as such surveys often now incorporate EPC assessments.

CIH has undertaken research work on adapting to climate change, linked below, and would be pleased to provide further information and evidence on this matter.

- Scott, M. (2025) Towards ‘futureproofed homes’: the implications for UK housing of a warming world. In CIH (2025) UK Housing Review

- Khosravi, M. and Scott, M. et al. (2025) A nation unprepared: Extreme heat and the need for adaptation in the United Kingdom, Energy Research and Social Science. [open-access pre-print available here]

- Scott, M. and Yesudas, N.M. (2025) Turning up the heat: nine discussion questions on overheating in domestic homes in the UK. Available here.

Furniture provision:

Research by End Furniture Poverty reveals that 6 million people in the UK live without essential items of furniture, furnishings or appliances, 1.2 million of whom are children, and 2,6 million are disabled. This can include not having a bed to sleep in or cooker to provide meals or washing machines for clean clothes. This has a huge impact not only on physical and mental wellbeing but social interaction and potentially on finances (such as debt if /when acquiring the necessary items).

CIH is aware of a number of landlords that are working with End Furniture Poverty to ensure that a percentage of the homes they let are furnished and / or include a furniture package, particularly in the case of households that have been homeless.

Government could build on the work of these landlords to demonstrate the benefits for residents and landlords, and how to incorporate this into their wider work on DHS and social benefit.

2035.

We would support 2035 as the most realistic and aspirational date for full implementation. Whilst earlier action would be desirable, the sector is already under huge financial pressure. Providers are dealing with inflation, net zero and retrofit demands, building safety, and the cost of living crisis, alongside a shortage of staff and materials in some areas. Setting a date much earlier without the money and roadmap to enable it would make the standard undeliverable.

2035 gives a ten-year window from when the standard is likely to be finalised. That matches the timescales used for the first Decent Homes programme, which also took around a decade to roll out. It gives landlords space to plan, sequence works properly, and align with other big national priorities like Awaab’s Law, net zero, and health and safety reforms.

We believe that this can work, if the following are considered:

- There is phased implementation, with core health and safety elements delivered sooner.

- Government sets interim milestones to keep momentum.

- Funding is targeted at landlords with the biggest retrofit and resource challenges.

Without that support, some landlords simply won’t be able to meet the standard, and we risk ending up with patchy delivery and bigger inequalities between providers. Delays beyond 2035 would also risk losing the momentum created by the Social Housing Regulation Act, Grenfell Inquiry recommendations, and Awaab’s Law.

2035 but see also Q49c.

Yes.

There are some issues impacting on the safety and health of tenants most directly that landlords should make effort to address in advance of 2035, as identified as landlords build their knowledge of their homes and households within them, to prioritise action. The Regulator of Social Housing can ensure that progress is made in these cases, and keep engagement with landlords as it has previously in cases of damp and mould.

The priorities for implementation should be identified by landlords and the Regulator, according to the issues emerging within different stock profiles, and for different households. We think this may include issues such as (not exhaustive):

- Damp and mould: We believe this should complement the phased approach around Awaab’s Law, recognising that damp and mould are among the most harmful hazards faced by residents.

- Basic health and safety requirement: We feel it's evident that tackling category 1 hazards are the most serious risk to health and therefore should not be delayed.

As above we have also suggested that a joint government and sector led approach to explore pathways to introduce floor coverings (how, when, at scale) might also be part of early work in advance of the start date for the DHS. As well as prioritising resident health, safety and well-being this reflects our most recent member engagement that there is support across the sector for more preventative action on health-related risks, even when the sector is facing wider pressures. It supports our aims of the Better Social Housing Review which stress the importance of ensuring homes are safe, decent and warm.

CIH has submitted its response to the government’s consultation on social rent convergence, in which we have called for £2 a week convergence with the necessary addition of funding for existing homes, to meet the regulatory requirements of DHS, minimum energy efficiency standards (MEES) and the introduction of the Heat Network Technical Assurance Scheme (HNTAS), alongside other measures. In the long term, the DHS could provide the framework under which other improvements sit, aligning existing and future funding streams to provide flexibility to landlords to streamline and plan improvement and refurbishment strategies. This would also help to time interventions and limit disturbance for residents.

Yes – however only in clear cases where a resident has genuinely refused the work. The standard should not enable circumstances where refusal is used as a barrier to effectively engaging with a resident to ensure that they are properly supported or informed. We understand that many providers already work in this area with respect to gas checks to ensure they get this right, so we know a degree of flexibility is important. The Housing Ombudsman has previously noted access as an issue, so it needs to be clear that refusals are recorded properly and that implications are clearly explained to residents. All avenues of support to try and resolve any concerns should be taken.

Yes, this would be welcome and helpful to ensure a more consistent approach. We would welcome the opportunity to work with officials on such guidance to help both providers and residents inform what is and is not a genuine refusal and define best practice to ensure residents are supported and treated fairly. We also feel that additional guidance would be helpful in terms of understanding how landlords are using this exemption.

Yes – it is likely that there will be situations where planning restrictions, listed or heritage status or the actual structure of a building may hinder or prevent compliance. Landlords should be encouraged to undertake those elements or criteria that they can that will improve the home, be cost effective and beneficial for tenants, rather than neglect the home entirely.

We believe that it makes sense to have some flexibility where a home is already scheduled for demolition or major regeneration and understand that this was the case in the 2006 standard. However, we are aware that in practice this can, and has, leave some residents living in poor conditions for too long because of the possibility of regeneration. Therefore, any exemption in this area needs to come with clear information for residents on what standards apply during that interim period whilst they remain in the property and timescales for future works, so that decency is not compromised over a long period of time for any resident.

We have several additional points:

We agree that a degree of flexibility will be needed in some cases, which will need to be clearly defined and then monitored. The Housing Ombudsman has highlighted cases where exemptions have created a barrier to progress when the issue was due to a lack of information, poor communication or a disagreement over process; therefore, we believe that the standard needs to be complemented with:

- Statutory guidance setting out when flexibilities can be used,

- Requirements for landlords to record and report their use, and

- Clarity for residents regarding their rights and route to challenge.

This then supports providers with clear expectations and helpful guidance whilst ensuring residents are protected.

By far the biggest challenge to meeting the Decent Homes Standard is the upgrading of pre-1919 stock. There are 1.5 million pre-1919 homes in England of which 1.4 million are private housing – 906,000 owner occupied and 533,000 private rented (as illustrated in the English Housing Survey 2023/24, drivers and impacts of housing quality).

Data from the English Housing Survey (EHS) 2020/21 shows that the average cost to make homes decent (to the current standard) in the private rented sector was the highest of any tenure being £8,475 per dwelling (£10,175 at 2025 prices) 55 per cent higher than for a social rented home and around eight per cent higher than for owner occupied dwellings. It also estimated 69 per cent of private rented homes required investment of £5,000 or more (£6,000 at 2025 prices) to meet band C, compared to 62 and 74 per cent of social rented and owner-occupied homes respectively.

A significant challenge for policy makers looking for ways to encourage investment is the fact rent levels are primarily determined by location and not property conditions. Worse still is the fact is that the increase in rental value that can be obtained from carrying out repairs is substantially less than the repayments required to finance it. However, some older studies have found a link between average rents and some aspects of the old fitness standard and tenants are more likely to consider the standard of facilities (such as in the kitchen and bathroom) rather than cost of major repairs when deciding what they are prepared pay. The fact that tenants value facilities over repairs is also reflected in the rents of furnished tenancies where landlords can expect to receive between 15 and 20 per cent more than they would for letting it unfurnished. This suggests that that a DHS that combines improved facilities (such as floor covering and modern kitchen/bathroom) with repairs is more likely to be successful in encouraging landlords to invest rather than an approach where enforcement is solely targeted at disrepair and the removal of hazards.

CIH supports the Government’s approach to the DHS for private renters as set out in the Renters’ Rights Bill. We agree that assessment and enforcement should run in parallel to the Housing Health and Safety Rating System. If enforcement against hazards and non-decent homes become separated there is danger that the new standards might take priority over hazards in ways that compromise resident safety. For example, the installation of cladding/insulation and inadequately supervised retrofitted facilities may result in compromised fire compartmentation.

As things currently stand, a private landlord can choose not to apply the PAS2035 process for non-grant funded work. There is a strong financial incentive not to do so because the end-to-end compliance can cost up to £2.000. Private landlords also contract out EPC assessment to private domestic energy assessors (DEAs) who can carry out the work if they have a level 3 qualification. An EPC certificate for retrofit works should not be issued if those works have compromised fire safety. Or at the very least if the PAS2035 process has not been followed that should be stated on the certificate together with a summary of the works done. Where PAS2035 has not been followed it should also be a requirement to notify the local authority who still have duty to act against category 1 hazards. The landlord and their contractor could choose to cover any liability created by the works through appropriate insurance.

Another challenge is encouraging small landlords to invest who may not have the same access to finance as larger landlords as well as the difficulties associated with engaging with a sector that is so disparate. Small landlords dominate the sector with just over half of private rented tenancies let by landlords that own between one and four properties. Given the difficulties that smaller landlords may face raising the finance this may suggest a longer period might be required to raise private rented homes to band C than for social rented homes. One option might be to allow a longer lead in time for smaller landlords which may also help local authorities approach enforcement more strategically.

Selective licensing is one of the few strategic tools available to local authorities to improve conditions. CIH welcomes the recent decision by the government to give general approval to new schemes so that the Secretary of State’s confirmation is no longer required. Following general approval, local authorities can set up selective licensing in areas with a high proportion of privately rented homes if significant numbers of those homes require inspection to determine whether they have category 1 or 2 hazards, but under the Renters’ Rights Bill this extends to inspections to determine type 1 or 2 requirements under the DHS. While hazards and type 1 and 2 requirements will often coincide, this won’t always be the case. For example, the authority may have already carried out a selective licensing scheme that has since run its course but would not be able to start a new scheme to tackle DHS deficiencies. Once part three of the Renters’ Rights Bill is commenced, we suggest that the additional conditions order is amended to take account of this.

The Chartered Institute of Housing (CIH) is the independent voice for housing and the home of professional standards. Our goal is simple – to provide housing professionals and their organisations with the advice, support and knowledge they need. CIH is a registered charity and not-for-profit organisation so the money we make is put back into the organisation and funds the activities we carry out to support the housing sector. We have a diverse membership of people who work in the public and private sectors, in 20 countries on five continents across the world.

- Sarah.davis@cih.org, policy manager

- Eve.blezard@cih.org, policy lead